Last week, I saw Lynette Yiadom-Boakye’s solo show at The New Museum, in New York. Yiadom-Boakye is a youngish portraitist, much-talked about. Some of the chatter is generated by greatly exaggerated reports of the death of portraiture, or figurative painting more broadly; some because both she and her subjects are black. Mostly, though, people are talking about her work for the best reason: because it defies explanation and so people are exhausting their words trying to explain it. Powerful, compelling: she receives–and deserves–all the best adjectives. No one calls the pictures beautiful, because that would be reductionist, and who wants to make beautiful art these days? Zadie Smith does point out that the subjects are beautiful, without entering into what this really means: that they don’t challenge educated middle class viewers ideas of human beauty: the subjects are thin and well-dressed and in clean, well-lighted spaces.

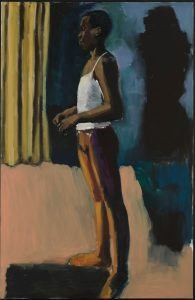

Beautiful, right? I could look at this all day long.

A number of critics, including whoever wrote the wall-note at the show, want to discuss the significance of the fact that the paintings don’t have models, that Yiadom-Boakye paints from imagination. My DH was skeptical, pointing out, “That makes no difference to how we see the art. It’s just a ‘conceptual’ layer people want to apply to her work because they think contemporary art must be ‘conceptual’ to seem relevant.” I think he’s right, even while I was undeniably intrigued by this factoid–how does a painter create individualized portraits without living, breathing human anatomy to interpret?–but it’s not hard to admit that all portraits are ultimately imagined, whether portraits of ‘real’ people with their names attached or, say, paintings of the Holy Family where the artist used his mistress as a model for the Madonna. Although it’s an interesting glimpse into Yiadom-Boakye’s process, it’s another dodge if you’re talking about the work.

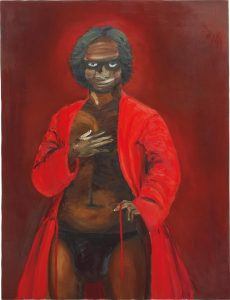

What I haven’t seen so much is discussion of how her work has changed. Just a few years ago, Yiadom-Boakye was doing portraits that were far less realistic and less idealized at once, more confrontational, wilder.

Here, too, color and the handling of light are key to the viewer’s experience of being compelled and seduced but the painting’s aura is unquiet, with nothing of the calm that permeates her latest show. There is a sense of movement captured: as with the newer works, the figure doesn’t feel posed so much as caught.

But maybe comparative discussions, too, are dodges and instead of adding the the chatter, I should just look and try to see.